0:00 - Introduction

This is a paper called "Does Dividend Policy Foretell Earnings Growth?" by Cliff Asness and Robert Arnott. Back in the 60s, Miller and Modigliani developed the Dividend Puzzle phenomenon, which states that investors should be indifferent as to the level of dividends a company pays (because the dividend or foregone dividend is either put in his own pocket to reinvest or kept in the company's pocket to reinvest on his behalf; he doesn't lose or gain wealth in either scenario).

Although elegant, the authors want to understand whether that thought process has proved to be true throughout history; and whether investors should take into consideration the level of dividends when making investment decisions. And in fact, one might be swayed to believe that if a company retains more of its earnings for reinvestment, then the company should exhibit higher earnings growth going forward, and vise versa. So does dividend policy foretell earnings growth?

1:14 - Exhibit 1. S&P 500 Payout Ratio

First, to get an idea of the average amount of dividends that have historically been paid out as a percentage of earnings, the authors have charted the S&P 500's dividend payout ratio (i.e., dividends divided by earnings) from 1950 - 2001.

They find that the historical payout ratio averages around 50% and is volatile, because dividends tend to be sticky, while earnings move up and down over time. At the date of this paper (i.e., 2001), the payout ratio was at its lowest level in recent history.

2:09 - Exhibit 2a. Payout Ratios and Subsequent ten-year Earnings Growth

Next, the authors want to understand whether historical payout ratios have had any bearing on future earnings growth (and indirectly, whether the Miller Modigliani dividend indifference theory holds). By creating a scatter plot with the historical payout ratio on the x-axis and the subsequent 10-year earnings growth on the y-axis, they find a positive relationship between the two; for example, the higher the payout ratio (i.e., the less earnings are being retained), the higher the next 10-years' earnings growth. This is the complete opposite of what might be expected (i.e., one would think if the company retained more earnings, they would likely see more earnings growth in the future; but that's not the case according to this figure).

3:03 - Exhibit 2b. Ten-year Earnings Growth, as function of Payout Ratios

For additional analysis, the authors create regressions over various time periods going back to 1871, with the 10-year earnings growth as the dependent variable and the payout ratio as the independent variable. They find over all time periods that the coefficient on the payout ratio is positive in all time periods and statistically significant. As such, this analysis supports the prior figure in confirming that higher payout ratios have resulted in higher earnings growth over the next 10 years.

3:44 - Exhibit 3. Payout Ratios and Subsequent ten-year Earnings Growth

Next, the authors split the payout ratios of the population into quartiles (i.e., 4 groups) to assess the amount of earnings growth (i.e., the average, maximum, and minimum) at different levels of payout ratios. They find that the average subsequent 10-year earnings growth increases as the quartile of payout ratios increases; and in fact, the quartile with the lowest payout ratio exhibited negative earnings growth. Further, the worst earnings growth period in the highest payout ratio quartile exhibited higher earnings growth than the average payout ratio at the lowest quartile of payout ratios. They found a monotonically increasing relationship of payout ratios and subsequent 10-year earnings growth.

5:19 - Potential Explanations for the Positive Relationship of Payout to Growth

The authors have come up with several reasons why this counter-intuitive result might be occurring:

- Management prefers not to cut dividends: If management prefers not to cut dividends (because it makes the company look bad), they would want to pay out a level of dividends that is sustainable; therefore, the dividend policy might be a reflection of management's confidence in the stability and growth of future earnings. As such, if management is fairly sure the future earnings growth is attainable, they would be more comfortable paying out more dividends. And in that case, higher payout ratios might foretell future earnings growth.

- Marginal attractiveness of reinvestment opportunities: If management has several projects that it can reinvest the earnings in, then it will select the best projects first and each subsequent project will be marginally less profitable. As such, if management retains a lot of earnings, then it might be forced to reinvest them in less compelling projects. Therefore, a higher payout ratio might force management to be more selective in the projects it invests in; thereby efficiently managing the company's capital. And in that case, higher payout ratios might foretell future earnings growth through efficiency and reinvestment selectivity.

- Empire building: Management might retain too much of its earnings, which gives them the incentive to possibly spend frivolously. With less earnings retained, management might be more frugal, reduce conflicts of interest, and perhaps curtail empire building. And in that case, a higher payout ratio might foretell future earnings growth through better management of cash and expenses.

- Sticky dividends and mean reversion of earnings: Earnings might be temporarily depressed (which produces high payout ratios, because dividends amounts are generally less volatile), then move back up to their long-term mean; thereby giving that appearance that high payout ratios predicted high earnings growth, when in factor it was just the nature of earnings volatility.

- Data or experimental design error: The results might be isolated to the period under study, but might not be true across other time periods not studied; the results might be due to another economic variable (as opposed to the payout ratio); or perhaps the recent increase in share repurchases are being done in lieu of dividends, causing misinterpretations of the payout ratios and earnings per share.

8:24 - Exhibit 2b. Robustness Test Over Time Periods

For the first robustness check, they go back to exhibit 2b and look at the different time periods under study. The initial time period under study was 1950 - 2001, which showed supporting results for the positive relationship between the payout ratio and subsequent 10-year earnings growth. So, they next performed the same regression over the 1926 - 2001, 1871 - 2001, and 1871 - 1941 time periods, finding the same results as before (albeit, a bit muted); as such, it does not appear there is an error of isolated time period.

9:54 - Exhibit 4a. Earnings Growth as function of Prior Earnings Growth

The next robustness check is to test the possibility that maybe the positive relationship between payout ratio and subsequent earnings growth is merely the result of mean reversion of earnings and sticky dividends. The authors created a regression that has 10-year earnings growth as the dependent variable and both payout ratio and lagged 10-year earnings growth as the independent variables. If high earnings growth (and a high payout ratio) is due to a reversion of earnings upward to the long-term mean, then we would expect a negative coefficient on the lagged 10-year earnings growth variable (because earnings would have had to go down previously, resulting in their go back up to the mean in the subsequent 10 years).

The authors find the coefficient on the lagged 10-year earnings growth variable is not statistically significant; so we might conclude that the prior earnings growth is not related to the future earnings growth; and as a result, the positive relationship of payout ratio and subsequent 10-year earnings growth does not appear to be caused by a mean reversion of earnings and sticky dividends.

11:47 - Exhibit 4b. Earnings Growth as Function of Current dividend by 20-Year Avg

As a second robustness test of the potential for the reversion of earnings to their mean, the authors prepared the same regression; only this time, they replace the lagged earnings variable with a ratio of current earnings to the prior 20-year average of earnings. As in the prior regression, if the coefficient on the ratio of current earnings to 20-year average is negative, then we might conclude that earnings were temporarily depressed and merely reverted to their mean, thereby causing a positive relationship between earnings growth and payout ratios. Instead, they find the same result as before: the coefficient on the ratio of earnings to 20-year average is statistically insignificant and therefore determined to not explain the subsequent 10-year earnings growth. As such, we again find that the positive relationship between payout ratios and subsequent earnings growth is likely not caused by a mean reversion of earnings and sticky dividends.

13:28 - Exhibit 5. Five-Year Growth as function of Payout Ratios

Next, as another robustness test, the authors form a regression to see the relationship between payout ratios and subsequent 5-year earnings growth (whereas, prior exhibits were of 10-year earnings growth); by reducing the 5-year periods, the authors are adding more individual data-points to the analysis at the sacrifice of longer time periods. They find the same results as before where the payout ratios are significantly positively related to the subsequent five-year earnings growth.

Next, as a robustness check of whether the recent propensity to repurchase shares in lieu of paying dividends, the authors form the same regression; only this time they halt the time period at 1979, because this is around the time that companies started taking part in more stock buybacks. If these share buybacks are affecting the payout ratios (i.e., companies are repurchasing shares instead of paying dividends), we would expect a less significant relationship between the payout ratio and earnings growth. But instead, we still find a significant and positive relationship between the payout ratio and earnings growth before 1979; and the 1980 - 2001 period even has a 50% R^2, suggesting that this regression explains a very large portion of the variation in returns, even though more dividends are potentially being "paid out" as stock buybacks.

16:03 - Exhibit 6. Consistency of R2 and T-Stat

Next, the authors want to understand how consistently the a + b*PR regression has explained the variation in 5-year earnings growth over time. To do so, they do this regression on 30-year rolling periods and plot the R^2. They find that the R^2 is fairly volatile, ranging from 0.15 to 0.63, but is always at a respectable level.

Next, the authors chart the t-statistics of the coefficient on the payout ratio for the 30-year rolling a + b*PR regression. They find the t-statistic is always at a significant level (except for maybe the 1910ish period), signaling that the payout ratio significantly explains the subsequent 5-year growth throughout the entire time period under study.

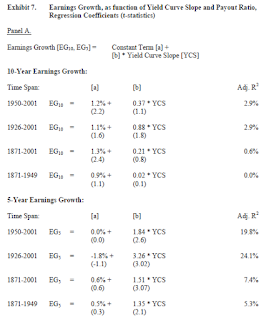

17:57 - Exhibit 7. Growth as function of YCS and Payout Ratio

Next, the authors want to understand whether other economic variables might be causing the significance of the positive relationship between payout ratios and subsequent earnings growth (rather than the payout ratios themselves). To do so, they form regressions with the 5 and 10 year earnings growth as the dependent variable and the yield curve slope (i.e., the ratio of 10-year treasury to 3-month treasury) as the independent variable. Historically, higher yield curves have predicted higher earnings growth. The regression on the 10-year earnings growth results in an insignificant coefficient on the yield curve variable; however, the regression on the 5-year earnings growth results in significant and positive between yield curve slope and 5-year earnings growth over all time periods under study.

To determine whether this yield curve slope is supplanting the payout ratios, the authors formed a regression with 5 and 10-year earnings growth as the dependent variable and the payout ratio and the yield curve slope as independent variables. In both cases, they find that the yield curve slope is statistically insignificant and the payout ratio is positively and significantly related to the subsequent 5 and 10-year earnings growth. As such, the yield curve slope is a poor predictor of subsequent earnings growth when compared with the explanatory power of the payout ratio.

20:48 - Exhibit 8. Ten Year Growth as function of earnings yield and payout ratio

Finally, as another example of another variable that might be supplanting the payout ratio as a powerful explainer of subsequent earnings growth, the authors form the same regression as above, only this time they've replaced the yield curve slope variable with an earnings yield (i.e., earnings divided by price) variable. They do find that earnings yield is a significant predictor of earnings growth on its own; however, its explanatory power is crushed when payout ratios are added to the regression. As such, the payout ratio is much better at predicting earnings growth than is the earnings yield.

As such, in assessing/predicting future earnings growth, it might be more prudent to follow the lead of company management (i.e., by paying attention to their dividend policy) than to investors (i.e., by paying attention to P/E levels).

Abstract

Many market observers point to the very high fraction of earnings retained (or low dividend payout ratio) among companies today as a sign that future earnings growth will be well above historical norms. This view is sometimes interpreted as an extension of the work of Miller and Modigliani. They proved that, given certain assumptions about market efficiency, dividend policy should not matter to the value of a firm. Extending this concept intertemporally, and to the market as a whole, as many do, whenever market-wide dividend payout ratios are low, higher reinvestment of earnings should lead to faster future aggregate growth.However, in the real world, many complications exist that could confound the expected inverse relationship between current payouts and future earnings growth. For instance, dividends might signals managers' private information about future earnings prospects, with low payout ratios indicating fear that the current earnings may not be sustainable. Alternatively, earnings might be retained for the purpose of "empire-building," which itself can negatively impact future earnings growth.

We test whether dividend policy, as we observe in the payout ratio of the market portfolio, forecasts future aggregate earnings growth. This is, in a sense, one test of whether dividend policy "matters." The historical evidence strongly suggests that expected future earnings growth is fastest when current payout ratios are high and slowest when payout ratios are low. This relationship is not subsumed by other factors such as simple mean reversion in earnings. Our evidence contradicts the views of many who believe that substantial reinvestment of retained earnings will fuel faster future earnings growth. Rather, it is fully consistent with anecdotal tales about managers signaling their earnings expectations through dividends, or engaging in inefficient empire building, at times; either of these phenomena will conform with a positive link between payout ratios and subsequent earnings growth.

Our findings offer a challenge to optimistic market observers who see recent low dividend payouts as a sign of high future earnings growth to come. These observers may prove to be correct, but history provides scant support for their thesis. This challenge is potentially all the more serious, as recent stock prices, relative to earnings, dividends and book values, rely heavily upon this expectation of superior future real earnings growth.

No comments:

Post a Comment